Buried In The Suburbs

Posted on May 4, 2025

I had the initial idea of making these little box works probably more than a year ago but making art in the face of a full blown attempt to exterminate a people can stop you in your tracks. The idea that I could make anything meaningful at all, much less in the tin box format of the Attempts to Stop Death series seemed ridiculous, and crass. Even the series title seems inept and over-reaching. The alternative though is to say nothing and I feel that saying nothing is fundamentally the wrong thing to do. On the marches that have been such a feature of the campaign of opposition to the slaughter there is a chant – ‘When Gaza is under attack, what do we do? Stand Up! Fight Back!’ and that is really the only option. As an artist I make art. It’s not always great art but it’s here, it exists in the world and it is an attempt to stand up, to fight back.

The title ‘Buried In The Suburbs‘ derives from a song by Pony Club, a London-based band whose members came from Dublin. The song is about the banality, the mundanity of much of what we do on a day to day basis – We’ve got a hatchback silver Focus, like every other family around us – and it came to me when I was thinking of how there is nothing particularly distinctive about the people being bombed in Gaza. They live in their nondescript houses, drive unremarkable cars, carry out the same repetitive tasks and hold down the same boring jobs as people everywhere. The only thing that marks them out as distinctive is the hatred that is foisted upon them, a hatred that they never asked for and which they do not want.

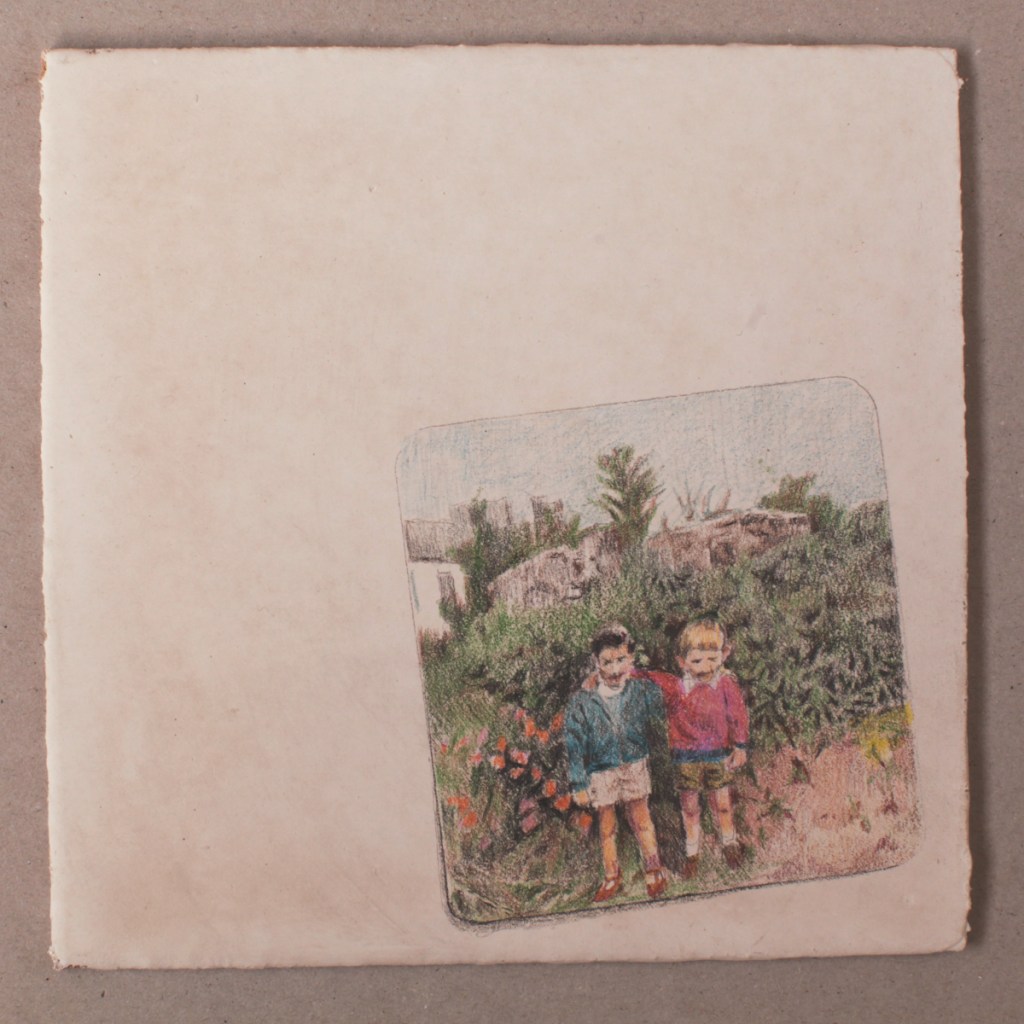

Two Little Boys

Posted on May 4, 2025

I’m not the most sentimental of people. My mother was famously unsentimental and would happily throw out anything that couldn’t prove itself to be of some practical use. I’m not quite as ruthless but the fact that I’ve moved dozens of times over the years means I’m fairly light on personal effects. A while ago my friend John sent me a photograph of us, we could be five years old in it, possibly six, out the back of his childhood house. I’ve known him since I was born, our mothers wheeled us round in prams together, I formed my first band with him, he moved away to work, so did I, we kept in touch but sporadically. We both moved back eventually. When I was waiting for surgery and not allowed to drive he took me shopping. Just before my surgery was due he had a heart attack and died in a shopping centre. A passing nurse with the presence of mind to shout for a defibrillator got him back. We’re probably closer than ever. Treasure your friends, the thread of life is tenuous.

Death and His Manservant

Posted on December 19, 2024

I don’t particularly think of myself as a surrealist. When there are odd juxtapositions in my work they are normally planned and programmatic. Purposeful. This work though has its origins in accident. I broke a favourite cup a few years ago, trying to do six things at once as usual and the coffee stained the floor of the space I was using as a studio in those times. For some reason I was moved to trace around the outline of the stain and of a fragment of the broken cup. I stashed the drawing and it has moved countries with me twice. At some point I drew a brutish face beneath the ‘hat’ and, seeing a shambolic, shameful hooded figure I added two walking sticks to prop it up. I stashed it again and in the empty warehouse of my brain that shambolic figure became death. Sluggish and inept, unable to get about without help from its thuggish supporter it seemed obvious as this year ground on that I would locate this hideous pair in Gaza against a backdrop of shattered building and buried children. Death the occupation, his manservant the western capitalist powers which fund and arm it. I’d normally shy away from spelling these things out but nothing about this is normal, is it? In the first iteration Death was dressed in grey but I made a second pass, putting death in imperial purple. Empire is death.

Other People’s Pasts

Posted on December 6, 2024

One of the legends of Finn McCool tells of him being tricked by the Cailleach Beara who turns herself into a white deer and lures him into the volcanic lake at the summit of Slieve Gullion where he almost drowns. He gets out of this scrape, although I can’t remember how. I came across this photograph of a young man who decided to climb Slieve Gullion in the days when young men dressed in a suit and tie for all but the most casual of occasions. In my version of his story he stands astride the Cailleach Beara who has transformed herself into a giant rabbit resplendent with a crown, the lake swapped for a da Vinci-esque receding landscape. I know nothing of the context of the photograph and nothing of what became of him. Did he chase a white deer into the lake? Unlikely, I grant you but whatever, I don’t know his story so I’ve given him one of my own choosing.

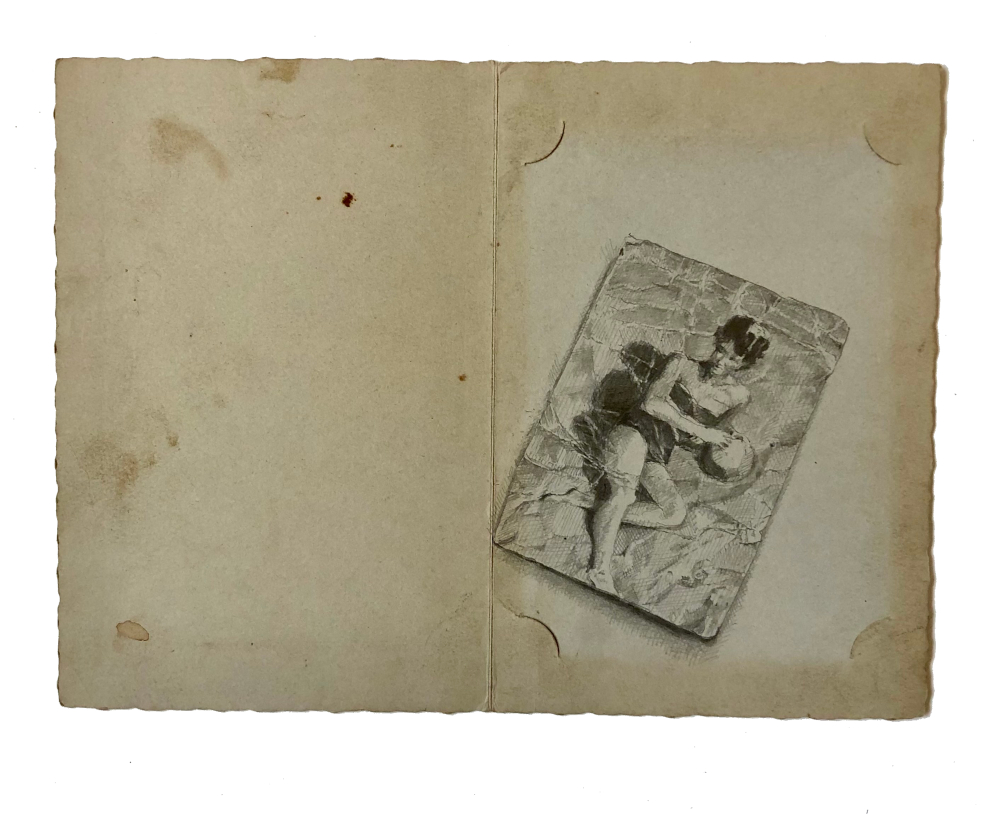

The Past Is A Foreign Country

Posted on December 6, 2024

When my mother died I inherited a couple of boxes of family photos. The bulk of them date to before I was born and some originally came to her from my uncle on his death. My uncle arrived home to Newry when I was a child and to my young eyes he was an exotic figure. He and a friend had run away to join the merchant marine in their youth and he came back via a long, untalked-of stretch of time in London where he plied the family trade of plastering and, apparently, drank anything he ever earned. He was a sharp dresser though, with a Sinatra-like sparkle and a ready wit. He is the source of the photo I transcribed for this work, some unrecorded, unknown friend or lover, whether from London or his prior travels I have no idea but a testament to the vivid colour of a life that faded to gray once he returned home.

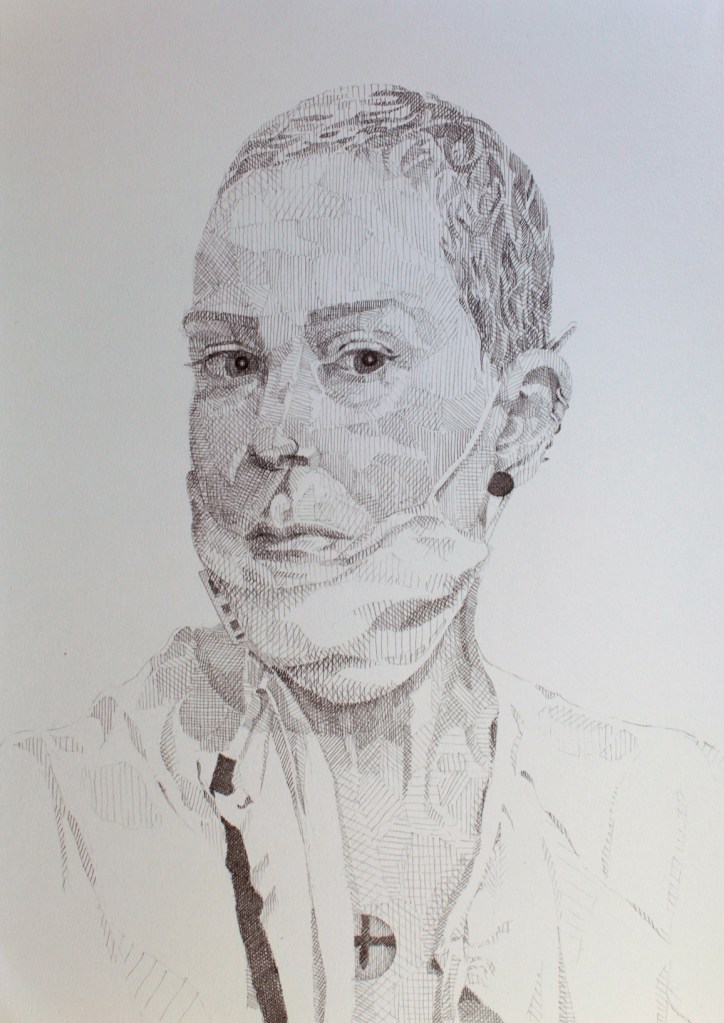

Still Drawing / Drawing Again

Posted on December 5, 2024

Drawing

Posted on February 6, 2023

Over the last couple of years I’ve made a preponderance of three dimensional work but a recent change of circumstance has forced me to re-think my practice. I’ve always had an interest in historic practices and the seemingly alchemical ways in which previous generations of artists used materials in inventive ways. One of the processes I’m particularly interested in is silverpoint. Before graphite lead pencils were in common use artists used a silver pointed stylus to make a mark. If you look at any old master drawings there’s a high degree of probability that the delicately traced marks they made were put on a prepared papaer surface with a silverpoint. The silver leaves no visible mark on bare paper but if you coat the paper with casein gesso it leaves a fine grey line. Once the mark is made it can’t be erased the way a pencil line can so it’s a very unforgiving technique but ineffably beautiful. I’m normally in favour of diving straight in but on this occasion I’ve decided I had better refresh my drawing abilities fo I’ll end up succumbing to frustration so what you’re seeing below are pencil drawings.

The Cold Hard Facts Of Life

Posted on November 10, 2022

This piece is on show as part of the Artists At Work 2 exhibition at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery until February 12th 2023. I had originally intended to show one of the works from the Three Views of A Border exhibition but I couldn’t get the dates to work. Three Views was still touring in Ireland when the work had to be delivered so I wavered, vacillated, huffed and puffed and decided to show this, which is the most complex of a series of related pieces that pull together memory fragments of the 1970s in a playful way.

It has a number of familiar elements. The lead and bitumen are there, as are George and Pat and the rusty drawing pins but there are ideas there that are still emerging and which I’ll develop in future. The gallery gets quite a high number of family visitors and the lower panel is hung at a child’s eye level which I really like, hopefully the magpie nature of the collage will be appealing to young visitors. That’s an approach I want to develop in future. In keeping with a lot of recent work the title ‘The Cold Hard Facts Of Life’ comes from a countrypolitan song, Porter Wagoner’s finest moment in this case, although the phrase ‘Pressure Cookers! Pressure Cookers!’ appears in typescript on the upper panel and I was almost swayed to use that as a title. One visitor has already likened the piece to ‘an explosion in a junk shop’. If that isn’t a title waiting for a piece I don’t know what is.

The Sin Eater

Posted on September 27, 2022

A lot of us carry our guilt around. It weighs us down. Almost everyone has done at least one thing in our lives which we’re deeply ashamed of and which we have an unhealthy habit of letting define us. The Sin Eater is a piece which aims to empower the viewer, or the actor because you interact with this work far more than you view it, to absolves themselves of that burden. First shown as part of Three Views of A Border in An Tain in Dundalk, The Sin Eater then travelled to the Cityside Arts Festival in Belfast and a second iteration is currently part of the Iontas incarnation of Three Views of A Border.

When an exhibition ends I unseal the ballot box and burn the ballots before encasing them in wax to produce a permanent record of those absolved sins.

I would love this to have a life independent, or semi-autonomous at least, of me. You don’t really need the ballot box, any box which can be sealed will do. If you contact me I’ll send you an instructions poster, and if you send back the ballots in a sealed envelope I will burn them and transform them into the outworking of the installation as you can see with The Sins Of Dundalk below.

Three Views Of A Border

Posted on September 27, 2022

Myself and my friend and fellow artist Anna Marie Savage have talked for a number of years about the possibility of exhibiting bodies of work together as we both grew up along the border and both have frequently made work in response to the experiences and memories of how life was and is there. We approached the Tain Arts Centre in Dundalk and they suggested we add Ciaran Dunbar to the mix. The resultant exhibition brought together three very different views of life in proximity to the border. Anna’s work is extremely painterly. Her sensuous use of paint and ink is a very effective counterpoint to the harsh, often angular intrusions into the landscape that serve as her visual starting point; Ciaran’s work as a documentary photographer interrogates life along the border in a detached fashion while my work examines how landscape and memory are codependent in our own experience of an ambivalent past. I’ve gathered together the body of work I made for the exhibition in the ‘It Only Hurts If You Look At It’ page of this site.

The exhibition was warmly received and a second venue came on board with the exhibition moving to the Iontas Theatre and Arts Centre in Castleblayney, Co. Monaghan in August. The modern space of Iontas gives the exhibition a radically different context from the exhibition space of the Tain Arts Centre which was originally a set of cells under Dundalk Court House. The exhibition continues there until October 25th 2022.